Case: On a day shift in the Emergency Department you receive a 27-year-old male returning from a climbing trip in Arizona. He was completing a 300m climb when he felt his finger « pop » and fell 12m. He did not sustained any serious injury from the fall but he explains that for a few days, he has been experiencing pain in his 4th finger. He kept on climbing despite the pain but now he is no longer able to extend his finger.

Take Home Points

- The « crimp grip technique« is the mechanism of injury

- This injury severity ranges from simple sprain to full pulley rupture

- Assess for severity of injury on physical exam

- Hand surgeon involvement is necessary for significant injuries

Rock climbing’s popularity has increased greatly in recent years. In 1988 there were only three climbing gyms in the US. By 2006, there were more than 700. In 2020, the Tokyo Olympics will feature rock climbing as one of it’s new disciplines. The sport has moved from being focused on adventure and danger (Mountaineering) to strength, technique and training (Indoor rock climbing). As a result, younger athletes are now presenting to the ED with acute and subacute MSK injuries rather than serious trauma from fall.

Mechanism and Presentation

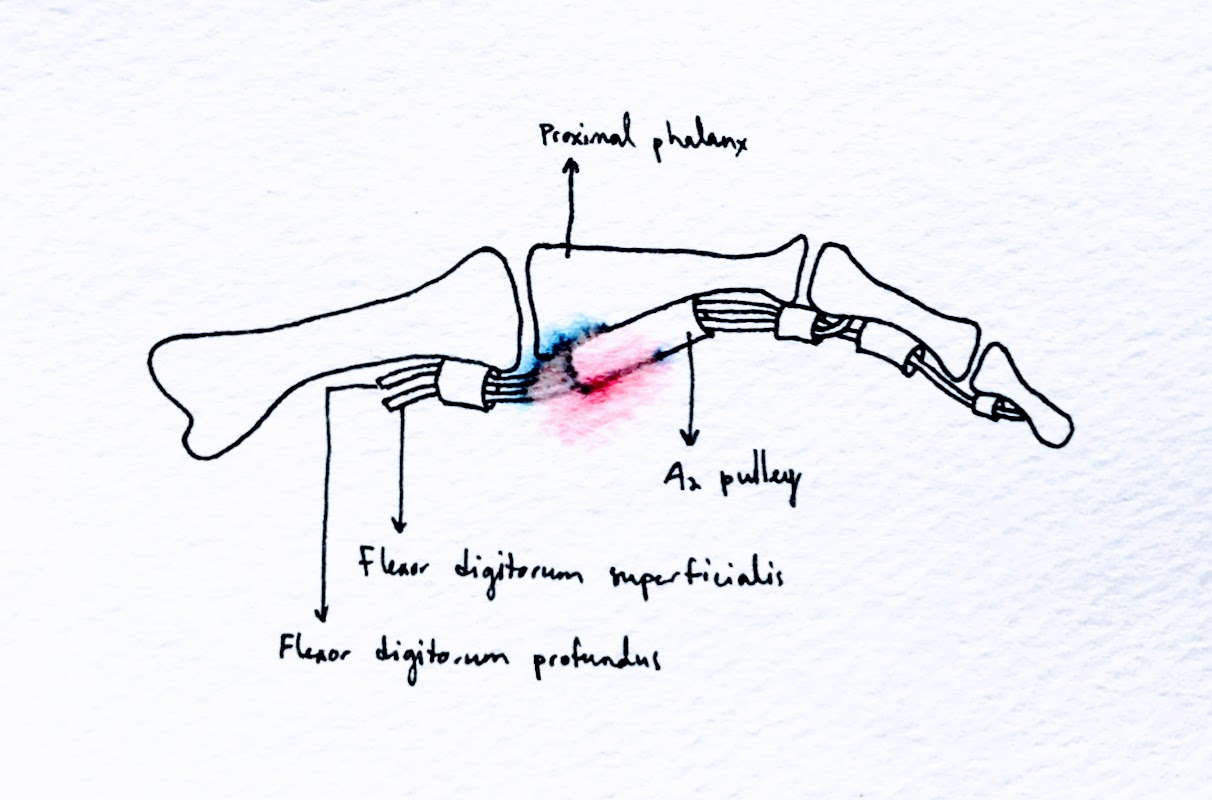

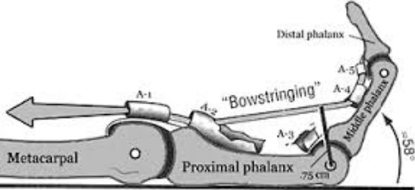

Also known as ‘’climber’s finger ‘’, A2 pulley injury is the most frequent injury, representing 30% of all injuries associated to climbing. It can range from a simple strain to a complete pulley rupture. The pulleys are tendon arrangements that hold the digital flexor tendon to the periosteum. A2 and A4 pulleys are the most important to accomplish the strong and precise flexion movements required in climbing. Anatomically, the A2 pulley is located at the mid portion of the proximal phalange. On the left 4th digit, the A2 pulley sits where your wedding ring would sit. A1 pulley is most commonly involved in trigger finger. The other pulleys are less clinically significant.

When climbing, most of the weight is located on the 3rd and 4th finger and the injury will almost always occur while doing a crimp grip, a technique used to hold the tiniest of holds. This technique generates large forces in the flexor digitorum profondus and superficialis tendons and when one puts too much pressure on the hand and not enough weight on the feet, or if the feet slips, injuries will occur.

The climber will frequently report hearing or feeling a pop in his finger followed by immediate pain and decrease in grip strength. Localized edema or bowstringing deformity may also be present.

The physical exam helps determine the severity of the injury. Evaluate the injured finger through full range of motion.Intermittent inability to extend the finger indicates a dorsal migration of extensor tendon. Bowstringing should be specifically searched as it indicates full pulley rupture. Careful palpation of all « A« pulleys should be done to identify multiple pulley ruptures which will present as local pain at the level of the injured pulleys.

Most climbers won’t stop their activity right after the injury. They will keep on climbing despite the pain by changing their technique. However, any kind of climbing will worsened the injury and increase recovery time. Some climbers won’t seek medical attention until a more significant injury or re-injury occurs

Treatment

In the ER, the patient should be placed in a supportive brace and should be advised to rest from climbing for 6 to 8 weeks. They should also be referred to specialized physiotherapy care for rehabilitation.

The patient should be referred to a hand surgeon from the ED if there is :

- Tendon bowstring

- Dorsal migration of extensor tendon (will present as an inability to extend the finger)

- Multi-pulley injuries

The climber may return to full activities within 3 months of the injury. Finger taping over the symptomatic finger should be continued for at least 6 months. It is a common misconception in the climbing community that taping is an alternative to rest, while on the contrary it is not. In fact, taping will not support the pulley enough to prevent worsening of injury.

References :

- Schöffl V et al , Injury trends in rock climbers: evaluation of a case series of 911 injuries between 2009 and 2012, Wilderness Environ Med. 2015 Mar;26(1):62-7. doi: 10.1016/j.wem.2014.08.013.

- Logan A J, Acute hand and wrist injuries in experienced rock climbers, Br J Sports Med. 2004 Oct;38(5):545-8

- McDonald J W, Descriptive Epidemiology, Medical Evaluation and Outcomes of Rock Climbing Injuries, Wilderness Environ Med. 2017 Sep;28(3):185-196. doi: 10.1016/j.wem.2017.05.001. Epub 2017 Jul 26.

- Pozzi A, Hand Injury in Rock Climbing: Literature Review, J Hand Surg Asian Pac Vol. 2016 Feb;21(1):13-7. doi: 10.1142/S2424835516400038.

- Daverport, P Tang, Chapter 268: Injuries to the Hand and Digits, Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide 8th Edition

- Karadsheh, Flexor Pulley System, Orthobullets.com. Updated 2016

Written by Jonathan Séguin-Bigras, CCFP-EM resident, McGill University

Reviewed by Chanel Fortier-Tougas